Womens Suffrage Societies were first founded in the late 1860s, and as the vote was gradually extended to all men, the issue of women’s rights came to the fore. 1898 saw the formation of The National Federation of Women’s Suffrage Groups, and in 1903, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was established in October 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel. This group was committed to “deeds, not words”, and the campaign became more direct.

Derby had a particularly active suffragette movement, and visits were made to the town by both Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. Throughout the country, attacks committed to support the suffragette movement intensified, and included several cases of arson, particularly against churches.

In 1914, Breadsall Church was destroyed by fire, an act which has always been credited to the local branch of the WSPU. A number of property-owners took steps to protect their property – the Miller Mundys at Shipley Hall, for example, had a large wall built close to the hall; this is still known as the ‘Suffragette Wall’.

And for the royal visit to Heanor in 1914, the local Church Lads Brigade were given the task of guarding St Lawrence’s church overnight to prevent any damage by the Suffragettes to the patriotic banner (“God Bless them Both”) hung there.

But the suffrage movement, whose membership ranged from the wealthy to working women, were equally involved in verbal campaigns, and were active in public meetings. Elections provided them with ideal opportunities.

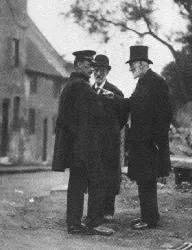

The Ilkeston Parliamentary Division (which included Heanor) had a by-election on 7 March 1910, after the sitting MP, Balthazar Foster, was promoted to the House of Lords, becoming the first Baron Ilkeston. A meeting was held at Heanor Town Hall on 2 March, at which the principal speaker was Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst (pictured on the right). The hall was densely packed, and hundreds of people were stood outside trying to get in. The following day’s newspaper recorded a lengthy series of questions to Mrs Pankhurst by Agnes Slack of Ripley. The Town Council were rather embarrassed that the leader of the Suffragettes had managed to get a booking at the town hall without their knowledge, and later in the same week they changed the procedure for renting the building! Similarly, at the by-election in 1912 (caused when the MP, Colonel Seely, was created the Secretary of State for War), suffragette activity was widespread: ‘six or more conveyances’ were driven around the constituency, ‘gaily bedecked with the well-known colours and profusely placarded with “Keep the Liberals out”’.

For everything that the Suffragettes sacrificed and achieved, it was the First World War that would prove to be their strongest rallying cry. ‘Women’s War Work’, a pamphlet printed in 1916, stated that women have shown themselves capable of successfully replacing the stronger sex in practically every calling. The idea of men being the ‘stronger sex’ might irk and rankle in the 21st century but back then this was the norm: women couldn’t vote, few could work in anything but domestic service or the textile trade, and divorce instigated by a woman was unheard of. The Suffragettes, and women in general, played their part actively to change this.

World War 1 saw thousands of men killed, men who would need to be replaced. Who would run the factories, dockyard, police stations, fire stations, transport depots and farms that they left behind? 1.6 million women were brought into the workplace, almost doubling the number of females previously in employment. Their efforts were finally rewarded on 6 February 1918 when the Representation of the People Act gave 8.5 million women over 30 (who, or whose husband, owned property) the vote. A further 6.5 million women aged over 21 were given equal voting rights with men in 1928.

Notable Suffragettes from Derbyshire:

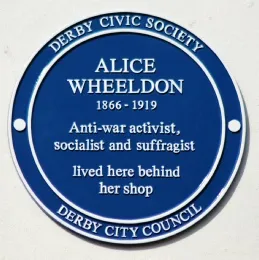

Alice Wheeldon

Alice Wheeldon was born in Derby in 1866 and died in Derby on 21 February 1919. She was the daughter of a locomotive driver, and when young worked as a house servant. She married and was subsequently estranged from her husband a mechanic who became an alcoholic. They had three daughters and a son – the son being refused the status of conscientious objector when he refused to be conscripted in 1916.

Alice was a member of the Socialist Labour Party, and the ‘No Conscription Fellowship’, as well as being active in the Women’s Social and Political Union. She and her family are known for sheltering young men fleeing conscription in Derby, and she supported herself by selling secondhand clothes from her house in Pear Tree Road.

On the 30 January 1917, Alice, along with two of her daughters, was arrested and all were charged with conspiracy to murder the Liberal Prime Minister Lloyd George and Labour Party Minister Arthur Henderson. Alice was sentenced to 10 years penal servitude and was sent to Aylesbury Prison where she went on hunger strike – she was later sent to Holloway. Alice, on the request of Lloyd George, was released from prison on licence on 31 December 1917.

Alice’s grave was never marked when she died, as there was concern that it would be defaced. A blue plaque now marks her home on Pear Tree Road, Derby.

Hannah Mitchell

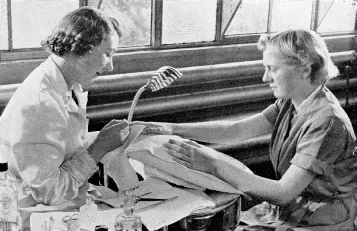

Hannah Mitchell (left) was born Hannah Marie Webster in 1872 – she died in 1956. Hannah was born in rural poverty in the extreme north of the county, near to the Snake Pass. After only a fortnight’s formal schooling, she fled the repression of home for the drudgery of domestic service and the misery of a clothing sweatshop.

Hannah became involved in the Socialist Movement and worked for many years in organisations related to socialism, women’s suffrage and pacifism. After the First World War she was elected to Manchester City Council and worked as a magistrate. Marriage and motherhood followed but her commitment lay in fighting the twin oppressions of sex and class which hampered her generation.

In 2012 the Hannah Mitchell Foundation was founded, a forum for the development of devolved government in the North of England. The name was chosen “in memory of an outstanding northern socialist, feminist and co-operator who was proud of her working class roots and had a cultural as well as political vision”. There is a blue plaque dedicated to her on the wall of the house where she lived in Ashton-under-Lyne between 1900 and 1910.

Our thanks go to Sharon Mee for her work on the information for this page.